The DNA of human embryos has been altered and studied for the first time in the UK, offering new insight into the early stages of human development.

Scientists at the Francis Crick Institute, a medical research center, have identified the role of a key gene that controls how embryos form during the first few days of development.

Understanding the biology behind these early stages could help in the discovery of ways to improve the success of in-vitro fertilization, offer some explanation into why some women experience miscarriage and offer general knowledge on how humans develop.

Studies in the United States have manipulated the genomes of embryos to help understand -- and fix -- gene mutations that lead to inherited diseases, such as heart conditions. But this is the first research to target human growth and development.

'Switching off' a crucial stage

Stopping a gene from working and exploring what happens when it's gone is a good way to find out the gene's purpose.

The team used a gene-editing technique known as CRISPR-Cas9 to switch off a particular gene involved in embryo development, known as OCT4. Blocking the functioning of this gene means the resulting protein, also called OCT4, cannot be produced, eventually halting an embryo's development.

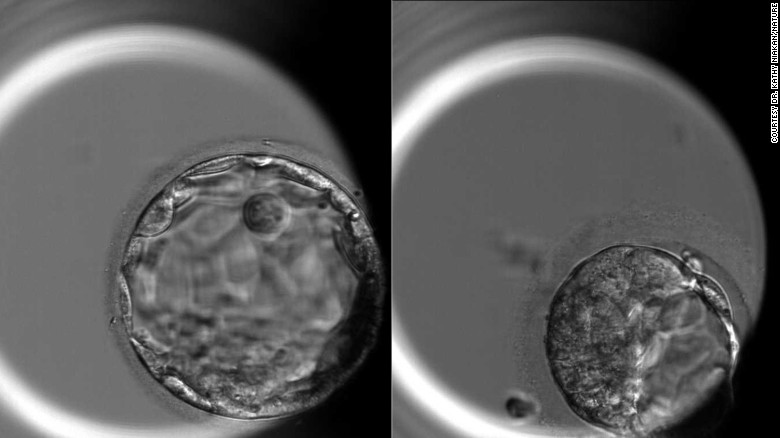

When a human egg is fertilized, it forms an embryo, which then divides and grows from one cell into a ball of more than 200 cells, called a blastocyst. At this point, the cells begin to separate and specialize, with some set to form the placenta and others destined to form a baby.

The researchers found that without OCT4, this blastocyst couldn't form."We were surprised to see just how crucial this gene is for human embryo development, but we need to continue our work to confirm its role," said Norah Fogarty of the Francis Crick Institute, first author of the study, which was published Wednesday in the journal Nature. "Other research methods, including studies in mice, suggested a later and more focused role for OCT4, so our results highlight the need for human embryo research," she said in a statement.

The new research investigated the role of this gene in mice and humans and found that OCT4 plays a different role in human embryos than in mice, highlighting the need for human research in this area.

"In humans, (OCT4) not only maintains the embryo, but other tissues are affected, and the blastocyst does not form," said Ludovic Vallier, a stem cell biologist at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute who co-authored the research. "In mice, (the gene) just maintains the integrity of the embryo."

The embryo on the fifth day of development, right, and an edited embryo without the OCT4 gene on the fifth day of development.

Vallier believes this further highlights that human development is very specific and and different from that of other species, meaning techniques based on animal models will have limitations. "We never know what to expect when we model from a mouse system," he said.

For the new study, the Crick Institute team blocked the OCT4 gene in 41 embryos donated by couples who had undergone IVF.

Opening the door for further research

After showing that gene-editing techniques can highlight the functionality of certain genes in this way, the team hopes other scientists will use these methods to discover the role of other genes and ultimately help improve IVF and avoid miscarriage.

Among women who know they are pregnant, it's estimated that one on six will have a miscarriage, according to the UK's National Health Service.

"If we knew the key genes that embryos need to develop successfully, we could improve IVF treatments and understand some causes of pregnancy failure," Kathy Niakan of the Francis Crick Institute, who led the research, said in a statement. This study opens the door for further investigations.

"It may take many years to achieve such an understanding. Our study is just the first step."

"This proof-of-principle paper uses CRISPR genome editing to show that although genetic expression in the early mouse embryo may be similar to a human embryo. There are critical differences in the levels and resulting developmental capacity of these embryos when essential genes are mutated," said Helen Claire O'Neill, programme director of reproductive science and women's health at University College London, who was not involved in the study. "This paper therefore elegantly highlights the need for further research using human embryos."

"One in every four couples has been affected by infertility, and to address the issue, we have to understand the biology of the earliest stages of human development," commented Dr. Dusko Ilic, reader in stem cell science at King's College London, who also was not part of the research. "The study is another proof that the findings from experimental animal models cannot be always extrapolated to humans."

This form of research, however, does not come without controversy, as it involved manipulating the genes of human embryos and the potential to alter the germline: how DNA is passed on though generations.

In the UK, strict ethical guidelines are in place for the use of eggs, sperm and embryos in research, regulated by the Human Fertilization and Embryo Authority. Researchers must apply for a license to conduct research, and embryos used for research cannot develop for longer than 14 days after fertilization and cannot be implanted into a woman's womb.

The new study explored blastocyst formation in embryos, which occurs within seven days of fertilization.

The controversy surrounding gene editing in human embryos partly stems from concern that the changes CRISPR makes in DNA can be passed down to the offspring of those embryos, from generation to generation. Down the line, that could affect the genetic makeup of humans in erratic ways.

Some CRISPR critics also have argued that gene editing may give way to eugenics and to allowing embryos to be edited with certain features in order to develop so-called designer babies.

But the researchers believe this does not apply to the current study, which focused on basic science and understanding rather than future editing in humans.

"We are focusing on developing the technology," Vallier said. "These proof-of-concept studies are needed to know the risks, to be sure there are no side effects and that the technique is not damaging other regions of the genome."

Many experts believe this form of research is pivotal to gaining a better understanding of how humans develop.

"There are many more questions posed by this first demonstration that genome editing can be added to the toolbox of methods that can be used to understand the biology of the early human embryo," said Robin Lovell-Badge, a geneticist at the Francis Crick Institute who was not involved in the study. "More understanding of the embryo itself will also lead to better ways to derive and use stem cells corresponding the various cell types that are present in the embryo shortly before implantation. Knowing which genes and the pathways they control will be key to all of this."

Source: CNN, Full Article