Efforts to heal the hole in Earth's ozone layer over Antarctica appear to be paying off, according to a new, first-of-its-kind study that looked directly at ozone-destroying chemicals in the atmosphere.

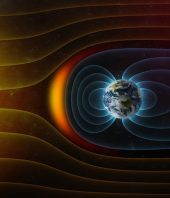

Earth's ozone layer protects the planet's surface from some of the sun's more harmful rays that can cause cancer and cataracts in humans, and damage plant life, according to NASA. In the mid-1980s, researchers identified a massive hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica and determined that it had been caused largely by human-produced chemicals called chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

Previous satellite observations have observed changes in the size of the ozone hole, noting that it can grow and shrink from year to year. But the new study is the first to directly measure changes in the amount of chlorine — the main CFC byproduct responsible for ozone depletion — in the atmosphere above Antarctica, according to a statement from NASA. The study showed a 20-percent decrease in ozone depletion due to chlorine between 2005 and 2016. [Earth's Atmosphere: Composition, Climate & Weather]

The new study looked at ozone data collected between 2005 and 2016 by the Microwave Limb Sounder (MLS) instrument aboard the Aura satellite. The instrument cannot directly detect chlorine atoms, but instead detects hydrochloric acid, which forms when chlorine atoms react with methane, and then bond with hydrogen. When Antarctica is bathed in sunlight in the Southern Hemisphere's summer, CFCs break down and produce chlorine, which then break apart ozone atoms. But during the winter months (early July to mid-September), the chlorine tends to bind with methane "once all the ozone has been destroyed" in its vicinity, according to the statement.

"By around mid-October, all the chlorine compounds are conveniently converted into one gas, so by measuring hydrochloric acid, we have a good measurement of the total chlorine," lead study author Susan Strahan, an atmospheric scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in the statement.

The MLS instrument observed the ozone hole daily during the Southern Hemisphere's winter.

"During this period, Antarctic temperatures are always very low, so the rate of ozone destruction depends mostly on how much chlorine there is," Strahan said. "This is when we want to measure ozone loss."

Because previous studies relied on measurements of the physical size of the ozone hole, the authors of the new study say their research is the first to directly show that ozone depletion is decreasing as a direct result of a decrease in the presence of chlorine from CFCs, according to the statement. The 20-percent reduction in depletion is "very close to what our model predicts we should see for this amount of chlorine decline," Strahan said.

"This gives us confidence that the decrease in ozone depletion through mid-September shown by MLS data is due to declining levels of chlorine coming from CFCs," she said. "But we're not yet seeing a clear decrease in the size of the ozone hole because that's controlled mainly by temperature after mid-September, which varies a lot from year to year."

The study was published Jan. 4 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Source: Live Science, Full Article