Four years ago, while searching for fish fossils on Madagascar, paleontologists came upon what proved to be a well-preserved cranium of a mammal that lived about 66 million to 70 million years ago, in the closing epoch of the mighty dinosaurs.

Such a discovery, expected to provide new and important insights into early mammalian evolution, is rare anywhere in the Southern Hemisphere. The fossil record of primitive mammals there is frustratingly thin. Only two other mammal skulls — both from Argentina and not as large — have been found from the age of dinosaurs in the entire Southern Hemisphere.

In a report published Wednesday in the journal Nature, David W. Krause, a paleontologist at Stony Brook University on Long Island and leader of the research team, announced that the fossil mammal is a distinct new genus and species, Vintana sertichi. Vintana means luck, which was smiling on Joseph Sertich, then a graduate student of Dr. Krause’s and now a curator at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, in finding the slab of sandstone that held the skull.

“No paleontologist could have come close to predicting the odd mix of anatomical features that this cranium exhibits,” Dr. Krause said in a statement.

The cranium, measuring almost five inches long, is twice the size of the one from the previously largest known mammal from the age of dinosaurs on the southern supercontinent known as Gondwana. At that time, nearly all primitive mammals were no bigger than shrews and mice, cowering in the shadows of hulking reptiles.

Vintana is estimated to have weighed about 20 pounds, twice or even three times the size of an adult groundhog today.

Though the researchers sometimes described the specimen as groundhog-like, Dr. Krause said that Vintana belonged to a lineage without any known living descendants. “It’s an entirely extinct lineage, an early experiment in mammals that didn’t make it,” he said in an interview. “And I doubt Vintana was any better at predicting seasonal weather change than Punxsutawney Phil in Pennsylvania.”

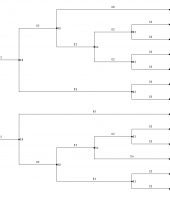

The researchers determined that Vintana belongs to a group of early mammals known as gondwanatherians, the only previous evidence for which were a few teeth and jaw fragments.

These mammals, in turn, were closely related to the multituberculates, an evolutionarily successful group of early mammals known almost exclusively from Northern Hemisphere fossils. All these relationships, scientists said, had been uncertain before now.

In a commentary accompanying the Nature paper, Anne Weil, an anatomist at the Oklahoma State University Center for Health Sciences, said the new findings offered “a cornucopia of data not only to solve” the mystery of the mammalian family tree “but also to reveal further astonishing morphological diversity among early mammals.”

Other researchers independent of the discovery team endorsed the interpretation of the findings. The study is “a remarkable achievement” and the cranium “is exceptional,” said Guillermo W. Rougier, a specialist in the early evolution of mammals at the University of Louisville.

An anatomist at the University of Chicago who is also an expert in mammalian evolution, Zhe-Xi Luo, called Vintana “the discovery of the decade for understanding the deep history of mammals.”

He said the study “offers the best case of how plate tectonics and biogeography have impacted animal evolution — a lineage of mammals isolated on a part of the ancient Gondwana had evolved some extraordinary features beyond our previous imagination.”

The first person at Stony Brook to see the CT image of the cranium embedded in the sandstone was Joe Groenke, a technician working with Dr. Krause. The specimen had wide eye sockets. Later analysis revealed teeth of a plant eater, and a nasal passage and inner ear of an animal with keen senses of smell and hearing.

“When we realized what was staring back at us on the computer screen, we were stunned,” Mr. Groenke said. He spent the next six months extracting the skull from the surrounding rock matrix, one sand grain at a time.

Source: New York Times

http://mobile.nytimes.com/2014/11/06/science/madagascar-fossil-vintana-mammals-evolution.html