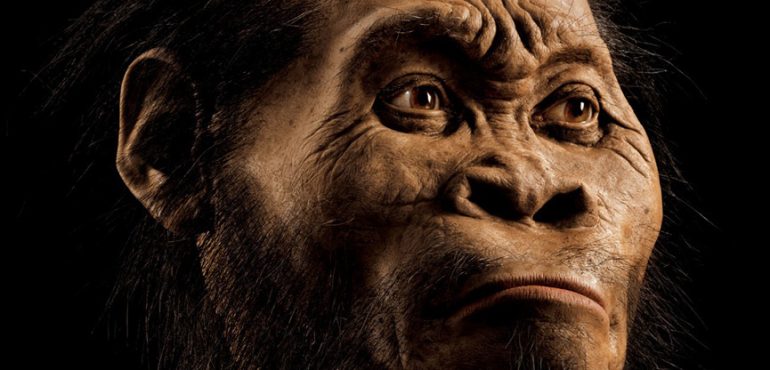

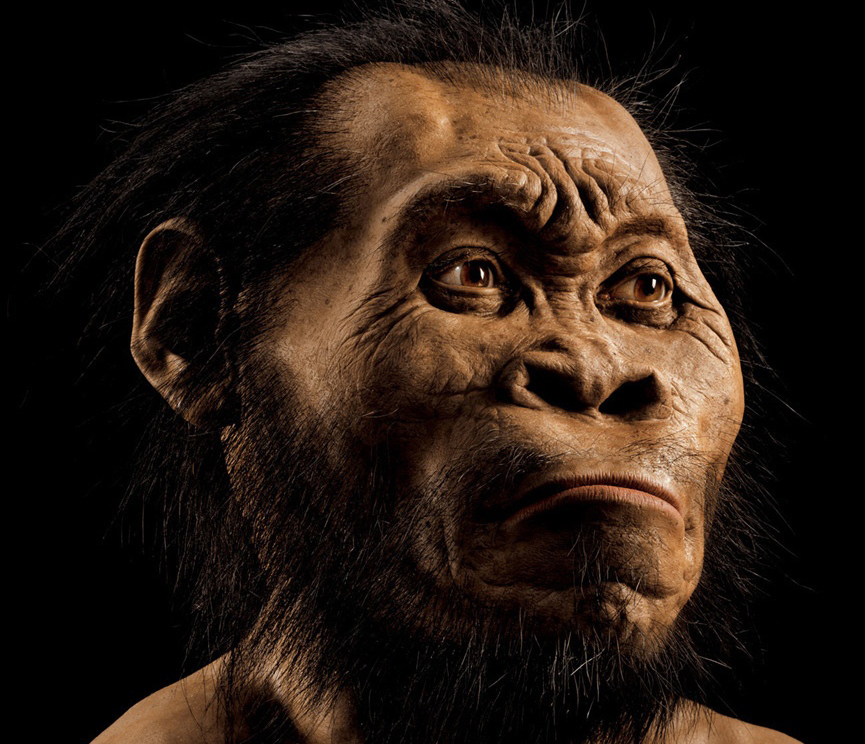

A newly discovered extinct human species may be the most primitive unearthed yet, with a brain about the size of an orange. But despite its small brain size, the early human performed ritual burials of its dead, researchers say.

This newfound species from South Africa, named Homo naledi, possessed an unusual mix of features, such as feet adapted for a life on the ground but hands suited for a life in the trees, that may force scientists to rewrite their models about the dawn of humanity.

Although modern humans are the only human lineage alive today, other human species once walked the Earth. These extinct lineages weremembers![]() of the genus Homo just as modern humans are. The earliest human specimens found yet are about 2.8 million years old. [See Images of the Newfound Human Relative]

of the genus Homo just as modern humans are. The earliest human specimens found yet are about 2.8 million years old. [See Images of the Newfound Human Relative]

Though the researchers aren't sure how far back this human relative dates, it is the newest addition to the genus Homo. "It's a very exciting finding," said paleoanthropologist Ian Tattersall at the American Museum of Natural History, who did not participate in this research.

However, Tattersall suggested these new hominins might not belong to genus Homo. "I'm a great advocate for the notion that the genus Homohas been made overinclusive," he said. "I don't like to stuff new things in old pigeonholes. I don't think we have the vocabulary needed to describe the diversity we're seeing in early hominins."

Underground astronauts

Two cavers, Rick Hunter and Steven Tucker, discovered the new fossils in 2013 in a cave known as Rising Star, locatedin the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site about 30 miles (50 kilometers) northwest of Johannesburg in South Africa. The species is named after the cave; "naledi" means "star" in Sesotho, a South African language.

The fossils were recovered in two missions in 2013 and 2014 dubbedthe Rising Star Expeditions. The bones lay in a chamber now named Dinaledi, meaning "many stars," located about 300 feet (90 meters) from the entrance of Rising Star.

Getting into Dinaledi required a steep climb up a sharp limestone block called "the Dragon's Back" and then down a narrow crack only 7 inches (18 centimeters) wide. A global![]() call for researchers who could fit through this chute resulted in six women chosen to serve as what the researchers called "underground astronauts."

call for researchers who could fit through this chute resulted in six women chosen to serve as what the researchers called "underground astronauts."

"They risked their lives on a daily basis to recover these extraordinary fossils," study![]() lead author Lee Berger, a paleoanthropologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, told Live Science. [See Photos of a Hominin that Lived Alongside Famous 'Lucy']

lead author Lee Berger, a paleoanthropologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, told Live Science. [See Photos of a Hominin that Lived Alongside Famous 'Lucy']

The scientists recovered more than 1,550 bones and bone fragments, a small fraction of the fossils believed to remain in the chamber. These represent at least 15 different individuals, including infant, child, adult and elderly specimens. This is the single largest fossil hominin find made yet in Africa. (Hominins include the human lineage and its relatives dating from after the split from the chimpanzee lineage.)

"With almost every bone in the body represented multiple times, Homo naledi is already practically the best-known fossil member of our lineage," Berger said.

"We will be trying to extract DNA from these fossils," Berger added.

A weird mix

On average, Homo naledi stood about 5 feet (1.5 m) tall and weighed about 100 lbs. (45 kilograms). It had a tiny brain, only about 30.5 cubic inches (500 cubic centimeters) in size, making the organ about as large as the average orange. That's smaller than the modern![]() human brain, which is about 73 to 97 cubic inches (1,200 to 1,600 cubic cm), but comparable in size to the brain of Australopithecus sediba. Australopithecines are likely the ancestors of the human lineage. [Australopithecus Photos: Anatomy of Humanity's Closest Relative]

human brain, which is about 73 to 97 cubic inches (1,200 to 1,600 cubic cm), but comparable in size to the brain of Australopithecus sediba. Australopithecines are likely the ancestors of the human lineage. [Australopithecus Photos: Anatomy of Humanity's Closest Relative]

Homo nalediwas a surprising blend of primitive and modern hominin traits. For example, "the hands suggest tool-using capabilities," study co-author Tracy Kivell of the University![]() of Kent in England said in a statement. Many scientists have long believed that tool use accompanied a boost in brain size, but Homo naledi's brain was rather small.

of Kent in England said in a statement. Many scientists have long believed that tool use accompanied a boost in brain size, but Homo naledi's brain was rather small.

In addition, its feet are virtually indistinguishable from those of modern humans. This, together with its long legs, suggest the species was adapted for a life on the ground involving long-distance walking. However,; its fingers were extremely curved, more curved than those of nearly any other species of early hominin, which hints at a life suited for climbing trees.

"Modern humans are really unusual in that walking on two legs is pretty much all we do," study co-author Will Harcourt-Smith, a paleoanthropologist at Lehman College in the Bronx and the American Museum of Natural History in New York, told Live Science. "Homo nalediprobably spent most of its time walking on two legs, but also spent some proportion of its time up in trees — whether to escape predators or nest at night, we don't know."

Furthermore, Homo naledi's small teeth, slender jaws and many skull features are similar to those of the earliest known members of Homo, but its shoulders are more similar to those of apes.

"The combination of anatomical features we see in this creature is not like any we've ever seen before," study co-author John Hawks, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, told Live Science.

Death rituals

Intriguingly, this primitive human species may have disposed of its dead repeatedly, a ritualized behavior previously confirmed only in modern humans.

"Homo naledi is a primitive member of our genus, perhaps the most primitive we've ever seen, but it had the capacity both mentally and behaviorally to dispose of remains in a ritual fashion," Berger said.

Dinaledi is an isolated part of the Rising Star cave system that was never open directly to the surface and attracted only a few accidental visitors. Of the more than 1,550 bones and bone fragments recovered from Dinaledi so far, only about a dozen are not hominin. These include the remains of small animals such as birds and mice.

There is no evidence that flowing water or mud washed these bones into Dinaledi, nor are there bite marks suggesting that predators or scavengers carried the remains into the chamber, nor cut marks suggesting cannibalism. Instead, the researchers suggest, these remains were brought into this remote spot intentionally over time.

Prior research had uncovered another possible instance of an extinct human species disposing of its dead, in Atapuerca in Spain. This site also contained remains thrown to the bottom of a cave. "Those hominins were much larger-brained, much closer to modern humans in brain size," Harcourt-Smith said. "There's debate as to which species was at Atapuerca — probably Homo heidelbergensis, a close relative of Neanderthals."

However, this is the first time such behavior with the dead has been seen with such a primitive hominin— that is, one dating back so early in the human family tree. "It's just an extraordinary discovery, a game-changer to see this very advanced behavior used back then," Harcourt-Smith said.

It remains unknown why Homo naledi disposed of its dead in this way. "We can spin a lot of yarns," Harcourt-Smith said. Maybe it buried the dead out of reverence, he said, or "maybe to get rid of things that were smelling. Maybe another species was throwing them down."

Uncertain place in the family tree

The age of the fossils remains uncertain, since the chamber lacks many of the features that scientists normally rely on to date fossils. As such, scientists can't yet say where Homo naledi fits on the human family tree. Depending on its age, it could be a direct ancestor to Homo sapiens, or the ancestor of the species that gave rise to Homo sapiens. "At this stage, all we know is that it's reasonably primitive," Harcourt-Smith said.

The researchers did note that both Homo naledi and the "hobbit" Homo floresiensis had similarly tiny brains. Although the scientists said they could not as yet speculate on any evolutionary links between those two species, the researchers new findings revealed that small-brained, primitive-looking human species with fairly modern features did exist in the past. This suggests that the hobbit is no longer an anomaly, the researchers said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Sept.10 in two papers published in the journal eLife, and reported their work in the cover story of the October issue of National Geographic magazine, as well as the NOVA/National Geographic Special "Dawn of Humanity," premiering Sept. 16.

Source: Live Science, Full Article