More than 3 million years ago, when “Lucy” was roaming the savannah of present-day Ethiopia, she may have encountered other two-legged apes not unlike her own species, Australopithecus afarensis—yet still just a wee bit strange.

Represented by jawbones from three individuals, a newly described species named Australopithecus deyrimeda adds to the scatter of evidence that not one, but a range of hominin species populated the East African landscape before 3 million years ago. This could imply they were able to carve out separate niches in a stable environment based on differences in diet, foraging strategies and other behaviors.

"We don't know enough yet to say anything about the nature of interaction or ecological differences between A. afarensis and A. deyiremeda,” says Stephanie Melillo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “We have to first know how to tell the two species apart from their fossil remains, and that is what this paper was all about."

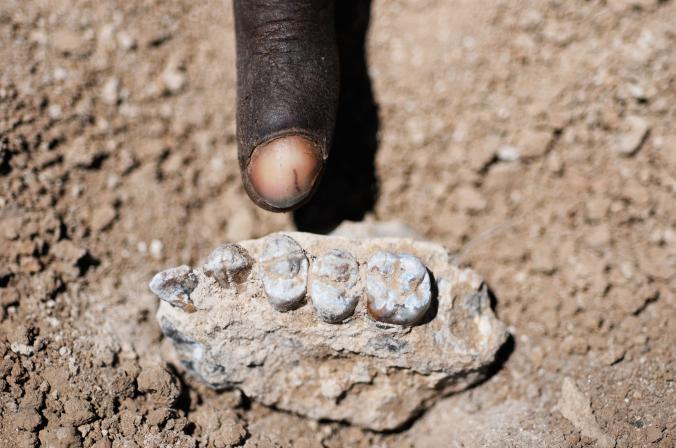

Reported Wednesday in Nature, the new specimens—a partial upper jaw, two lower jaws, and some other fragments—were found at Burtele, in the Afar Triangle of Ethiopia, just a day’s walk from Hadar, where Lucy was found in 1974. Sediments surrounding the bones were dated to 3.3 and 3.5 million years ago, a time when A afarensis is well known to have inhabited the region. While the new jaws share some characteristics with Lucy’s species, they differ in other respects. Some of the teeth have different root structures, and in general are smaller than A. afarensis teeth, a trait that could indicate a shift in diet.

“Smaller teeth are often associated with a more meaty diet,” says Fred Spoor of University College London and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “And the chewing muscles have migrated forward, which suggests a redistribution of chewing forces of some sort.”

The species name, A. deyrimeda, derives from the local words for “close” (deyi) and “relative” (remeda)—signaling the species close relationship with other hominins. But the similarities only go so far.

"We are convinced that it is different from A. afarensis. All of the evidence—published and unpublished—that we have from the localities at Burtele support our conclusion," says study author Yohannes Haile-Selassie of theCleveland Museum of Natural History. He notes that folding the new specimens into A. afarensis would introduce an extremely unusual amount of physical variation into the existing species.

Still, “the distinctions are very, very subtle,” says paleoanthropologist Bill Kimbel of the Institute of Human Origins. “I think the authors have done a very nice job in analyzing the material, but I think it’s a judgment call as to whether you think the differences amount to a species-level difference.”

A. afarensis remains by far the most conspicuous hominin in the fossil record of East Africa 3 to 4 million years ago, during a period known as the Middle Pliocene. But in the last two decades, scientists have named several others, including Australopithecus bahrelghazali from Chad, andKenyanthropus platyops from Kenya. A. deyrimeda further swells the crowd.

“There is now incontrovertible evidence to show that multiple hominins existed contemporaneously in eastern Africa during the Middle Pliocene,” the authors write.

Of special interest are some enigmatic foot bones of a hominin recovered in 2009 very close to where A. deyiremeda was unearthed. The bones suggest a creature with a flexible foot and big toe capable of grasping objects, similar to a more primitive hominin called Ardipithecus ramidus, dated to 4.4 million years ago. (Read about the discovery of Ar. ramidus in National Geographic Magazine.)

But perplexingly, the foot bones at Burtele date back to just 3.4 million years ago: the same time period as A. deyiremeda. It’s a combination of proximity in both space and time that cannot be ignored, Kimbel says.

“Figuring out whether or not that very primitive foot is the same critter as the clear australopithecine teeth and jaws that are being described now is of utmost importance,” Kimbel says. “It would mean that you could have australopithecus-like heads with more diverse options for locomotion – which is not a picture we have painted so far.”

Source: National Geographic, Full Article