Tardigrades are microscopic, resilient organisms that might just outlive the Sun—and their known world just got a little bigger.

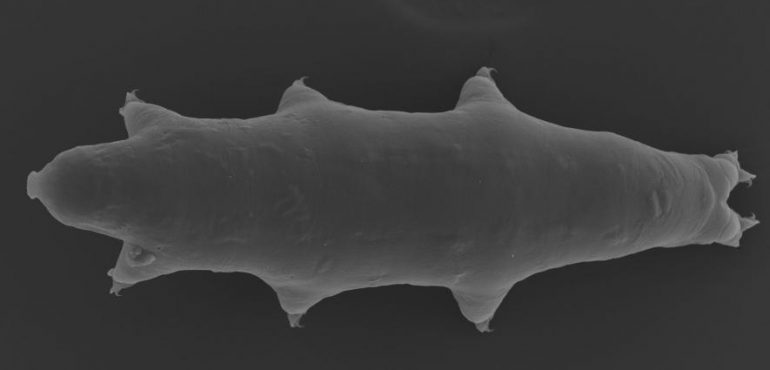

Kazuharu Arakawa, a researcher at Tokyo's Keio University, picked up a tardigrade specimen when he was gathering samples from the parking lot of his apartment building in Tsuruoka-City, Japan. He plucked a clump of moss protruding from the concrete and took it back to the lab for testing. After finding the micro-animal and analyzing its DNA, Arakawa and his Polish colleagues reproduced the tiny tardigrade. What sets this new species—named Macrobiotus shonaicus—apart from others is its chunky legs and bumpy eggs.

A paper with their findings was published Wednesday in the journal PLoS One.

DON'T MESS WITH THESE WATER BEARS

Tardigrades were first discovered in 1773 by a German zoologist, but they weren't fully characterized until a few years later. Also called "water bears" and "moss piglets," the creatures are plump, multilegged organisms that can be seen under a microscope. They have primitive eyes, measure around 0.02 inches long, and have been found in just about every environment on Earth, from the dark, deep sea and the humid, hot rainforest.

Although they spend their lives waddling around landscapes of moss, lichen, or leaf litter, tardigrades are easily the most resilient creatures known to science. They can live for decades, and fossilized tardigrades have been found to date back more than 500 million years.

Scientists have been testing tardigrades for years, heating them up to 300 degrees and freezing them to –328 degrees Fahrenheit. They've also sent the water bears to space and back. In these extreme environments, the animals will enter a type of hibernation called cryptobiosis, in which they recoil into a compact, dried ball and stay dormant for an indefinite period of time. A few years ago, a thawed tardigrade survived after being frozen for 30 years. They can suspend their metabolisms and survive immense amounts of pressure, and they've also been zapped with X-rays. (Related: read about what the world's toughest animal is made of.)

"Tardigrades are extremely hard animals," University of North Carolina postdoctoral fellow Thomas Boothby told National Geographic in 2017. "Scientists are still trying to work out how they survive these extremes."

This new species is the 168th to be discovered in Japan. (Worldwide, there are more than 1,000 different species of tardigrades, and about 20 new species are found each year.) The visual organs, mouths, spotting, and leg shape of M. shonaicus are similar to those found in other tardigrades, but this new species has an extra fold on the inside surface of its legs.

The spherical, solid eggs produced by M. shonaicus are different, too, pockmarked with chalice-like protrusions topped with a ring of flexible, stringy filaments. Arakawa says these protrusions might help the eggs attach to the surface where they're laid.

M. shonaicus is particularly similar to two other known species of tardigrade, one from Africa and another from South America. That means this new species could be a descendent of an ancient strand, which could give some insights into how tardigrades have diversified and adapted over time.

ONE TOUGH MOSS PIGLET

The tardigrade's ability to withstand freezing temperatures could help scientists create freeze-dried vaccines. These materials can be stored at higher temperatures than traditional vaccines, and only need to have water added just before they're used. The dehydration resistance of water bears could help inform scientists on how to preserve biological material, like cells, crops, and meats.

"Tardigrades are as close to indestructible as it gets on Earth," Rafael Alves Batista, a water bear researcher at the University of Oxford, told National Geographic last year. "But it's possible that there are other resilient species examples elsewhere in the universe."

Source: National Geographic, Full Article