It’s not quite a dinosaur, but maybe it could play one on T.V.

A research team led by scientists from Yale and Harvard have tweaked the activity of proteins in a chicken embryo to create a chicken with a reptile-like face. As dinosaurs slowly transitioned into their avian descendants, their snouts gradually morphed into beaks. Bringing those snouts back is part of an attempt to reverse engineer dinosaurs, which birds evolved from 150 million years ago.

Their first step was to identify why bird faces look different from reptile faces. The research team noticed that the cells that make two proteins involved in facial development have a different pattern in developing birds compared to developing reptiles. To see whether these proteins were important for beak formation, they infused a tiny bead with protein inhibitors and implanted it in the developing chicken embryo’s face.

Ewen Callaway, reporting for Nature, describes what they saw:

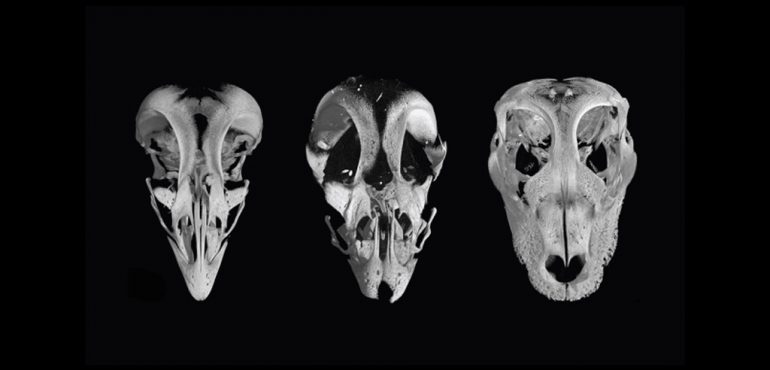

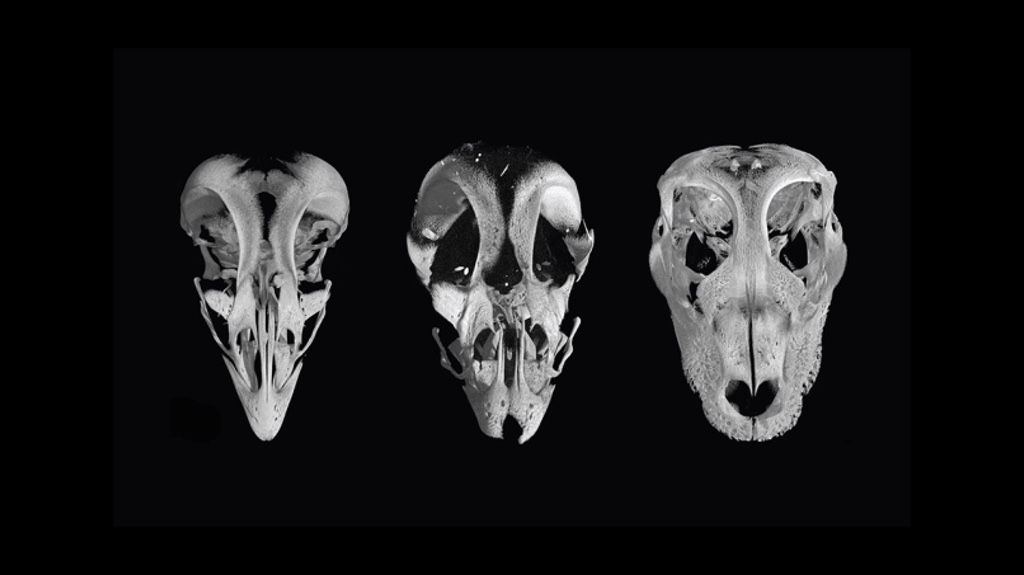

The researchers did not actually hatch the eggs, says Bhullar, because they did not write that step into their approved research protocol. Instead, they discerned differences in the faces of ready-to-hatch chicks, which looked subtly different from chicks without their proteins inhibited. The altered chicks still had a flap of skin over their would-be beaks, so the difference is not obvious, says Bhullar. “Looking at these animals externally, you would still think it’s a beak. But if you saw the skeleton, you’d just be very confused,” he says. “I would not say we gave birds snouts.”

In some embryos, the premaxillae were partly fused, whereas in others the two bones were distinct and much shorter; some of the altered embryos did not look all that different from those of regular chickens. The team created digital models of their skulls with a computed tomography scanner and found that some of these more closely resembled the bones of early birds such as Archaeopteryx and dinosaurs such as Velociraptor, than unmodified chickens.

This research was published online by the journal Evolution on Tuesday, and the scientists responsible for it don’t love the dino-chicken moniker. “Our goal here was to understand the molecular underpinnings of an important evolutionary transition, not to create a ‘dino-chicken’ simply for the sake of it,” says Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar in a news release. Bhullar is the assistant professor at Yale who led the study.

Their findings have received mixed reviews from the scientific community,reports Carl Zimmer for the New York Times. Some express concerns that the protein inhibitors were too blunt an instrument to learn much about the actual effects of these proteins—others thought the results were promising. Either way, this adds to the growing scientific movement of using pharmaceutical and genetic tools to understand creatures that have long been extinct, or haven’t yet been born.

Source: NOVA, Full Article