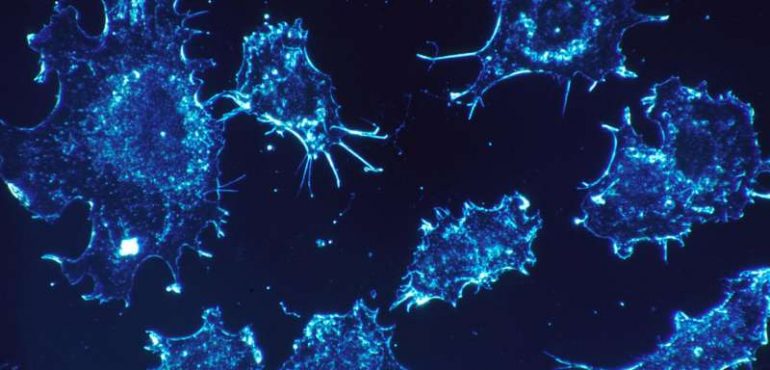

Salk researchers have discovered how to curb the growth of cancer cells by blocking the cells' access to certain nutrients. The approach, detailed in a new paper published today in Nature, took advantage of knowledge on how healthy cells use a 24-hour cycle to regulate the production of nutrients and was tested on glioblastoma brain tumors in mice.

"When we block access to these resources, cancer cells starve to death but normal cells are already used to this constraint so they're not affected," says Satchidananda Panda, a professor in the Salk Institute's Regulatory Biology Laboratory and lead author of the paper.

The circadian cycle, the intrinsic clock that exists in all living things, is known to help control when individual cells produce and use nutrients, among many other functions. Scientists previously discovered that proteins known as REV-ERBα and REV-ERBβ are responsible for turning on and off cells' ability to synthesize fats, as well as their ability to recycle materials—a process called autophagy—throughout the day. In healthy cells, fat synthesis and autophagy are allowed to occur for about 12 hours a day when REV-ERB protein levels remain low. The rest of the time, higher levels of the REV-ERB proteins block the processes so that the cells are not flooded with excessive fat synthesis and recycled nutrients. In the past, researchers developed compounds to activate REV-ERBs in the hopes of stopping fat synthesis to treat certain metabolic diseases.

Panda and his colleagues wondered whether activating REV-ERBs would slow cancer growth, since cancer cells heavily rely on the products of both fat synthesis and autophagy to grow.

"We've always thought about ways to stop cancer cells from dividing," says Panda. "But once they divide, they also have to grow before they can divide again, and to grow they need all these raw materials that are normally in short supply. So cancer cells devise strategies to escape the daily constraints of the circadian clock."

Although cancer cells contain REV-ERB proteins, somehow they remain inactive. Panda's team used two REV-ERB activators that had already been developed—SR9009 and SR9011—in studies on a variety of cancer cells, including those from T cell leukemia, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, melanoma and glioblastoma. In each cell line, treatment with the REV-ERB activators was enough to kill the cells. The same treatment on healthy cells had no effect.

"Activating REV-ERBs seemed to work in all the types of cancer we tried," says Panda. "That makes sense because irrespective of where or how a cancer started, all cancer cells need more nutrients and more recycled materials to build new cells."

Panda then went on to test the drugs on a new mouse model of glioblastoma recently developed by Inder Verma, a professor in the Salk Institute's Laboratory of Genetics. Once again, the REV-ERB activators were successful at killing cancer cells and stopping tumor growth but seemed not to affect the rest of the mice's cells. Verma says the findings are not only exciting because they point toward existing REV-ERB activators as potential cancer drugs, but also because they help shine light on the importance of the link between the circadian cycle, metabolism and cancer.

"These are all fundamental elements required by all living cells," says Verma. "By affecting REV-ERBs, you get to the heart of how cells grow and proliferate, but there are lots of other ways to get at this as well."

Verma says his group is planning follow-up studies on how, exactly, the REV-ERB blockers alter metabolism, as well as whether they may affect the metabolism of bacteria in the microbiome, the collection of microbes that live in the gut. Panda's team is hoping to study the role of other circadian cycle genes and proteins in cancer.

Source: Phys.org, Full Article