Scientists have been tinkering with the DNA in humans and other living things for decades. But one thing has long been considered off-limits: modifying human DNA in any way that could be passed down for generations.

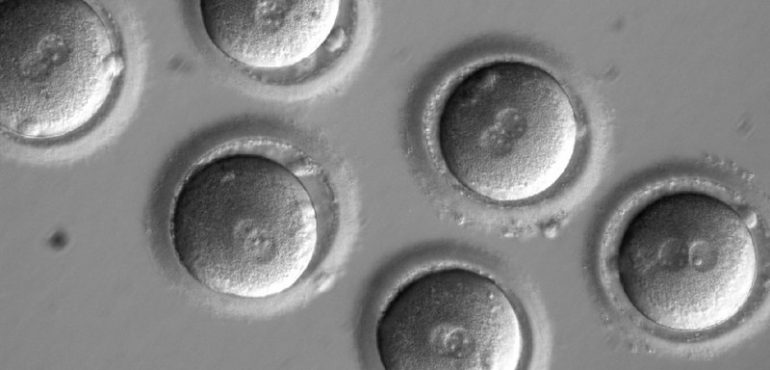

Now, an international team of scientists reports they have, for the first time, figured out a way to successfully edit the DNA in human embryos — without introducing the harmful mutations that were a problem in previous attempts elsewhere. The work was published online Wednesday in the journal Nature.

"It's a pretty exciting piece of science," says George Daley, dean of the Harvard Medical School, who was not involved in the research. "It's a technical tour de force. It's really remarkable."

The research is ultimately aimed at helping families plagued by genetic diseases. The new experiment used a powerful new gene-editing technique to correct a genetic defect behind a heart disorder that can cause seemingly healthy young people to suddenly die from heart failure.

The experiment corrected the defect in nearly two-thirds of several dozen embryos, without causing potentially dangerous mutations elsewhere in the DNA.

None of the embryos were used to try to create a baby. But if future experiments confirm the techniques are safe and effective, the scientists say the same approach could be used to prevent a long list of inheritable diseases.

"Potentially, we're talking about thousands of genes and thousands of patients," says Paula Amato, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. She was a member of the scientific team from the U.S., China and South Korea.

Other diseases that might ultimately benefit from such an approach include Huntington's disease, cystic fibrosis, perhaps an inherited form of Alzheimer's diseaseand cases of breast and ovarian cancer caused by mutations in the BRCA genes.

Nonetheless, the work is setting off alarm bells among critics around the world.

"I think it's extraordinarily disturbing," says Marcy Darnovsky, who directs the Center for Genetics and Society, a genetics watchdog group in Berkeley, Calif. "It's a flagrant disregard of calls for a broad societal consensus in decisions about a really momentous technology that could be used good, but in this case is being used in preparation for an extraordinarily risky application."

"If irresponsible scientists are not stopped, the world may soon be presented with a fait accompli of the first [genetically modified] baby," says David King, who heads the U.K-based group Human Genetics Alert. "We call on governments and international organizations to wake up and pass an immediate global ban on creating cloned or GM babies, before it is too late."

Amato and others stress that their work is aimed at preventing terrible diseases, not creating genetically enhanced people. And they note that much more research is needed to confirm the technique is safe and effective before anyone tries to make a baby this way.

But scientists hoping to continue the work in the U.S. face many regulatory obstacles. The National Institutes of Health will not fund any research involving human embryos (the new work was funded by Oregon Health & Science University). And the Food and Drug Administration is prohibited by Congress from considering any experiments that involve genetically modified human embryos.

Nevertheless, the researchers say they're hopeful about continuing the work, perhaps in Britain. The United Kingdom has permitted genetic experiments involving human embryos forbidden in the United States.

"If other countries would be interested, we would be happy to work with their regulatory bodies," says Shoukhrat Mitalipov, director of the Oregon Health & Science University's Center for Embryonic Cell and Gene Therapy.

Shoukhrat Mitalipov, principal investigator for the embryo editing study, directs the Center for Embryonic Cell and Gene Therapy at Oregon Health & Sciences University.

One major concern is safety to a developing embryo — whether genetically modified human embryos would indeed produce healthy babies. But on a broader level, any changes made in the DNA of an embryo would be passed down for generations. That raises fears that any mistakes in the editing that inadvertently caused new diseases could become a permanent part of that family's genetic blueprint.

Darnovsky and others also worry that modifying human DNA in an embryo could give rise to "designer babies." That's when parents pick and choose the traits of their children to try to make them smarter, taller, stronger or have other traits that make them seem superior. That's not yet technically possible. But critics fear scientists are already moving in that direction.

"The scenario is that you would have fertility clinics advertising to people who wanted to engineer their future children so that they could be presented as 'enhanced' — as biologically better than everyone else," Darnovsky says. "It's not a world we want to build. It's not a world we want to live in."

Unscrupulous researchers could also rush the technology into fertility clinics to try to start creating babies they can bill as genetically enhanced before the technology has even been proved safe, and before a societal consensus has been reached about what applications should be permitted.

"This is a strong statement that we can do genome editing," says Harvard's Daley. "The question that remains is: 'Should we?' We need a deeper public discourse around the ethical implications of this technology."

Darnovsky and some scientists argue that many couples who carry genetic diseases already have safer alternatives to this sort of gene editing. Couples carrying genetic diseases can go through in vitro fertilization (IVF) and have their embryos tested before being implanted in the womb.

"I will admit to experiencing a sense of puzzlement," says Fyodor Urnov, an associate director at the Altius Institute for Biomedical Sciences, a nonprofit research institute in Seattle.

"The question I have is: 'Why did you folks bother, given that there is a safe, effective, approved and ethical way to attain exactly the goal you have set out to do without any of the significant logical and ethic hurdles of having to edit a human embryo?" Urnov says.

Amato and the other scientists on the international team say their approach could offer an alternative for couples for whom those standard options won't work or are less desirable. But they agree the work should only move forward with careful regulatory oversight to prevent abuse.

"Anytime there's a new technology there's a potential for misuse. We have to acknowledge that," Amato says. "Personally I don't feel that's a reason not to pursue the research if you think there's a potential benefit that outweighs that risk. And I think if you can prevent serious disease in future generations, that makes it worthwhile to pursue this."

The advance was first reported last week in Technology Review, a magazine published by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But the details were withheld and the researchers did not elaborate until the scientific paper had finished being vetted by other scientists for publication in Nature.

For their experiments, the scientists obtained sperm from a donor carrying a mutation for the heart disorder cardiomyopathy. They then used that sperm to fertilize dozens of eggs obtained from healthy women.

At the same time as fertilization, the researchers injected a powerful, microscopic gene-editing tool known as CRISPR-Cas9. The new technique makes it much easier than previous approaches to make very precise changes in DNA.

Several scientists likened the approach to doing surgery on fetuses when they are in the womb. But this takes that idea much further and involves repairing damaged DNA at a molecular level in the womb.

"This is nano-surgery," says George Church, a prominent Harvard geneticist who also was not involved in the research. "You're doing it with the finest possible scalpel."

The editing tool very accurately cut into a mutated gene known as MYBPC3, which causes cardiomyopathy. To the researchers' surprise, the cut triggered the embryos to repair the defective gene on their own. This is a process that had previously been unknown, the scientists say.

"The most exciting moment was when we realized the mechanism of repair," Amato says. "It was fixing itself."

The researchers then let the embryos develop for several days so they could analyze them to see how well the experiments worked. In one part of the experiments involving 58 embryos, the approach corrected the mutation in more than 70 percent of the embryos, the researchers reported.

"The gene defect was corrected with high efficiency," Amato says.

In addition, a detailed genetic analysis of the embryos concluded that the gene editing had not caused safety problems.

"I think this is a significant advance," Church says. "This is important."

In 2015, Chinese scientists reported trying to edit the DNA of embryos for the first time, also using CRISPR-Cas9. But that experiment involved embryos that could never develop normally. And while those researchers did succeed in editing the targeted defect, it also produced unintended defects elsewhere in the embryos' DNA.

The scientists who conducted the new experiments say they think they avoided those problems by injecting CRISPR at the same time the eggs were being fertilized by sperm.

"That was key," Mitalipov says.

Alta Charo, a bioethicist at the University of Wisconsin, dismissed concerns about the work leading to designer babies.

"This is not the dawn of the era of the designer baby," says Charo, who co-chaired a committee formed by the National Academies of Sciences and the National Academy of Medicine to determine whether such experiments should be permissible. The committee concluded earlier this year that gene editing of human embryos could be allowed in rare cases when no other options are available — but only to treat diseases.

"I do not think that the constant drumbeat about the fear of designer baby is warranted, Charo says. "What this is, is a possible step toward being able to edit the DNA in human embryos that's reliable and precise."

In the meantime, scientists in Britain have won approval to use CRISPR to edit the DNA in healthy human embryos to learn more about normal human development. A team in Sweden has started similar experiments.

"I think this needs to be tightly regulated," says Fredrik Lanner, a geneticist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm who is conducting those experiments. "This is very exciting. But it also could be a double-edged sword. So I think we really have to be extra cautious with this technology."

Source: NPR, Full Article