Two species of bacteria work cooperatively to trigger colon cancer tumors, a study published Thursday reports.

The finding, which surprised the researchers, could eventually lead to new avenues for treatment.

Past research hinted at the potential importance of these bacteria to the development of colon cancer.

A 2015 study by Dr. Cynthia Sears and colleagues at the Sydney Kimmel Cancer Center, part of Johns Hopkins University, found that two bacterial strains invaded the mucus of the colon in people with colon cancer who were not genetically predisposed to it. Now, researchers from Johns Hopkins University studied people who have an inherited form of colon cancer and found that two particular types of bacteria were present in all cases.

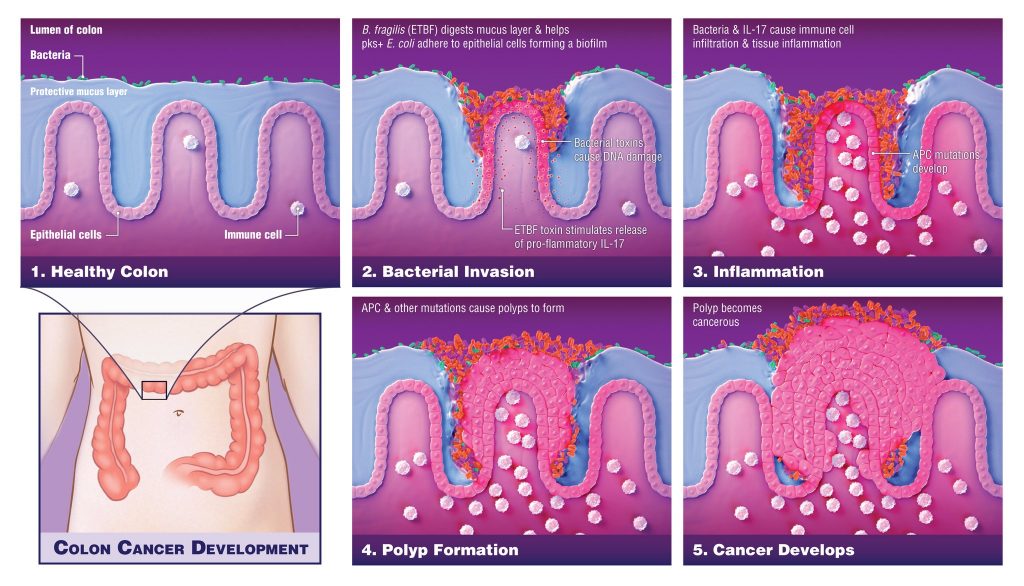

The finding surprised Sears and her team. Most bacteria can't travel past the protective layer surrounding the colon. But these two species—Bacteroides fragilis and Escherichia coli—could bypass this guardian and reach the epithelial cells, where tumors typically originate. Sears suspected that the bacteria had a hand in turning those cells cancerous.

To better understand the role of these bacteria species in colon cancer, Sears and colleagues examined colon tissue from six people with familial adenomatous polyposis, an inherited disorder in which polyps grow in the colon with a high risk of turning malignant. The researchers found that among the 500 types of bacteria known to live in the colon, B. fragilis and E. coli—the same species found in the prior study—were the most prevalent.

Sears has a theory about how these two species conspire to spur cancer: E. coli triggers genetic mutations and B. fragilis produces a toxin that promotes cancer. “It is the combination of these effects, requiring coexistence of these two bacteria, that creates the ‘perfect storm’ to drive colon cancer development,” Sears said in a statement. The study is published in the February issue of Science.

In addition to studying human tissue, the researchers also looked at mice. They found that when the colons housed colonies of both bacterial species at once, the mice developed a large number of tumors. When one or neither species was present, the mice had few or no tumors. The finding reinforced the notion that the species work together to trigger colon cancer.

The discovery could have practical applications. Finding a way to block the bacteria or the toxin produced by B. fragilis, could potentially prevent tumors from forming, Sears explained.

At the moment, we are powerless to stop these bacteria from colonizing the colon. And scientists don't know whether certain foods exacerbate the issue, said Sears.

The new study follows recent disconcerting news that colon cancer rates are rising among younger people, a trend that has surprised both experts and the public because this disease has always been tied to older age.

A report published last February showed the prevalence of colorectal cancer among 20 to 39 year olds increased from 1 percent to 2.4 percent since the 1980s. Thanks to better screening, cases have been declining since 1975, except in in this younger group, which surprised the study authors and medical community.

Rebecca Siegel, a public health expert with the American Cancer Society, said the rise in colon cancer among this younger age group is alarming in part because it's being diagnosed when patients are at the peak of their fertility.

She also wonders about how this spike will play out in coming decades. “Trends in young people are a bellwether for the future disease burden,” Siegel said in a statement. “Our finding that colorectal cancer risk for millennials has escalated back to the level of those born in the late 1800s is very sobering.”

Siegel said more emphasis is needed on preventing cancer. We may not be able to stop bacteria from entering the colon just yet. But, said Siegel, we can eat healthily, exercise and limit alcohol intake, all of which lower the risk of cancer.

Source: MSN, Full Article