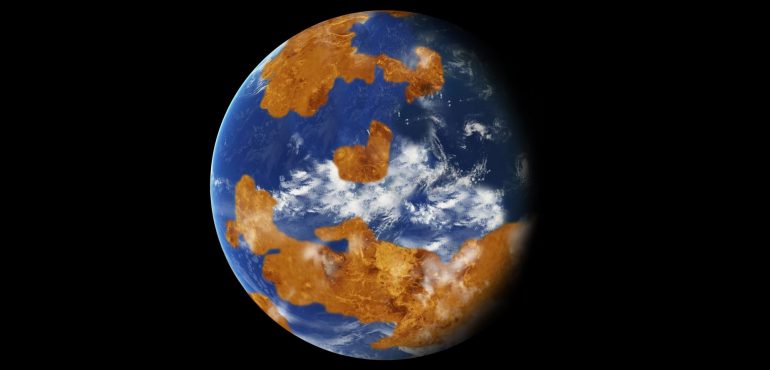

The hellish planet Venus may have had a perfectly habitable environment for 2 to 3 billion years after the planet formed, suggesting life would have had ample time to emerge there, according to a new study.

In 1978, NASA's Pioneer Venus spacecraft found evidence that the planet may have once had shallow oceans on its surface. Since then, several missions have investigated the planet's surface and atmosphere, revealing new details on how it transitioned from an "Earth-like" planet to the hot, hellish place it is today.

It's believed that Venus may have been a temperate planet hosting liquid water for 2 to 3 billion years before a massive resurfacing event about 700 million years ago triggered a runaway greenhouse effect, which caused the planet's atmosphere to become incredibly dense and hot.

Researchers from NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies shared a series of five simulations that show what Venus' environment would be like based on different levels of water coverage.

All five of the simulations suggest Venus may have been able to maintain stable temperatures, ranging from a low of 68 degrees Fahrenheit (20 degrees Celsius) to a high of 122 degrees Fahrenheit (50 degrees Celsius), for about 3 billion years, according to a statement from the Europlanet Society.

"Our hypothesis is that Venus may have had a stable climate for billions of years," Michael Way, one of the study researchers, said in the statement. "It is possible that the near-global resurfacing event is responsible for its transformation from an Earth-like climate to the hellish hot-house we see today."

Under stable climate conditions, Venus would have been able to support liquid water and, in turn, possibly allow life to emerge. In fact, if the planet hadn't experienced the resurfacing event, it might have remained habitable today, the researchers said.

However, the resurfacing event triggered a series of incidents that caused a release, or outgassing, of carbon dioxide stored in the rocks of the planet. As a result, Venus' atmosphere became too dense and hot for life to survive.

Creating the different simulations involved adapting a 3D general-circulation model, which accounted for atmospheric compositions as they were 4.2 billion years ago and 715 million years ago, and as they are today. The model also accounts for the gradual increase in solar radiation, as the sun gets warmer over the course of its lifetime.

In addition, three of the five scenarios assumed the topography of Venus was similar to what it is today. In these scenarios, the ocean ranged from a shallow depth of about 30 feet (10 meters) to about 1,000 feet (310 m), with a small amount of water locked in the soil.

For comparison, the researchers also considered a scenario in which the planet's topography was similar to Earth's with an ocean 1,000 feet (310 m) deep, as well as a scenario where the entire surface of Venus was covered in a 500-foot-deep (158 m) ocean, according to the statement.

"Venus currently has almost twice the solar radiation that we have at Earth. However, in all the scenarios we have modeled, we have found that Venus could still support surface temperatures amenable for liquid water," Way said in the statement. However, "something happened on Venus where a huge amount of gas was released into the atmosphere and couldn't be re-absorbed by the rocks."

Beginning 4.2 billion years ago, soon after the planet formed, Venus would have undergone a period of rapid cooling. As the planet evolved, silicate rocks would have slowly absorbed carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and locked it away in the planet's crust.

By 715 million years ago, the atmosphere of Venus would likely have been dominated by nitrogen with trace amounts of carbon dioxide and methane — much like Earth's today. The simulations suggest these conditions could have remained stable up until present times, if a massive outgassing event hadn't occurred.

While the exact cause of the outgassing event is still unknown, it's possible that it's linked to the planet's volcanic activity. As magma and molten rock bubbled up to the planet's surface, large amounts of carbon dioxide would have been released back into the atmosphere. If the magma had solidified before reaching the surface, it would have created a barrier and prevented gas from being reabsorbed, the researchers said.

Similar events have occurred in Earth's past. For example, the Siberian Traps is one of the largest known volcanic events in the last 500 million years. This event released toxic amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere and caused a mass extinction, the researchers said.

"We need more missions to study Venus and get a more detailed understanding of its history and evolution," Way said. "However, our models show that there is a real possibility that Venus could have been habitable and radically different from the Venus we see today. This opens up all kinds of implications for exoplanets found in what is called the 'Venus Zone', which may in fact host liquid water and temperate climates."

Their findings were presented Sept. 20 at the Joint Meeting of the European Planetary Science Congress and the American Astronomical Society's Division for Planetary Sciences (DPS), in Geneva.

Source: ABC News, Full Article